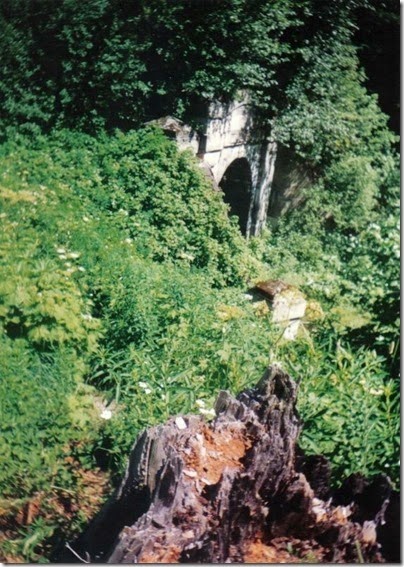

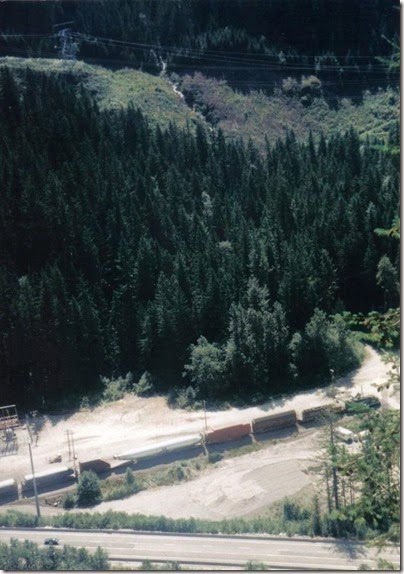

West Portal of the old Cascade Tunnel in 2000.

The tunnel between Scenic and Berne was not the first Cascade Tunnel. At the end of the Iron Goat Trail is the west portal of the first 2.63-mile Cascade Tunnel, built in 1900 between Wellington & Cascade Station. Before building this tunnel, the Great Northern used a series of switchbacks to get over the pass. The map below shows the switchbacks and the first Cascade Tunnel.

These switchbacks were part of the original route over Stevens Pass from 1893. The Great Northern always planned to tunnel between Cascade Station and Wellington, but James J. Hill was most concerned about completing the route to Seattle, so to speed the completion of the line, the 12-mile series of switchback was built as a temporary measure. The switchback route was slow and treacherous; trains has to reverse direction several times, ultimately running in reverse over the summit, as they climbed up steep 3% to 4% grades through sharp 12-degree curves to an altitude of over 4,000 feet, over 650 feet above Cascade Station, where the highest point would be with the tunnel in use. Trains were limited to 1000-feet in length, including three locomotives needed to pull trains over the switchbacks. There was never a serious accident over the switchbacks in the five years they were used, but they were a bottleneck; it took a train 75 minutes to travel the 12.5 miles of switchbacks.

Historical Photo:

View of switchbacks on west slope, 1907-08 (WSHS)

Before the switchbacks were built, the Great Northern's primary freight locomotives were 2-6-0 Moguls built by the Rogers Locomotive Works. With 20,085 pounds of tractive effort and 87,000 pounds of weight on their drivers, they could only handle 3 or 4 cars on the 4% grades of the switchbacks. In 1891, the Great Northern received 4-8-0 locomotives from the Brooks Locomotive Works for pusher and road service. They had 28,925 pounds of tractive effort with 132,000 pounds on the drivers, and introduced the Belpaire firebox to the Great Northern. In 1892 the Brooks Locomotive Works of Dunkirk, New York delivered 2-8-0 Consolidations for road service with 26,080 pounds of tractive effort, 120,000 pounds on the drivers, and 180 pounds of boiler pressure. Originally ordered for service in the Rocky Mountains, the 2-8-0s and 4-8-0s came to Stevens Pass in time to help complete the switchbacks. They could handle 4 or 5 cars on the 4% grades. Initially the switchbacks could only handle 7 or 8 cars, so the full potential of pusher engines could not be realized, but the switchbacks were soon lengthened to hold 10 to 12 cars.

An eastbound 25-car freight train would arrive in Wellington from Skykomish with a 2-8-0 Consolidation pulling and a 4-8-0 pushing. Traversing the 21 miles of 2.2% grades from Skykomish to Wellington at 5 to 6 miles per hour took 5 to 15 hours with water stops, meeting other trains, clearing rock slides, and other delays. At Wellington, the train would be broken into smaller trains of 10 to 12 cars for the trip over the switchbacks, with one or two locomotives on the front and another on the back. Seven-car passenger trains required three 4-6-0 locomotives, two on the front and one on the back, to cross the switchbacks. With luck, a train could get over the eight switchbacks to Cascade Station in an hour and a half, but in the winter the trip could take 36 hours. The normal rate of snowfall in Stevens Pass was 8 inches an hour, with 12 inches an hour common, and the snow often drifted 75 feet deep. The Great Northern employed hundreds of men to keep the switchbacks open and shovel out trains.

In 1898, the Brooks Works delivered to the Great Northern new 4-6-0s with 34,000 pounds of tractive effort, 130,000 pounds on the drivers, and 210 pounds of boiler pressures for passenger service and new 4-8-0s with 35,200 pounds of tractive effort, 172,000 pounds on the drivers and 210 pounds of boiler pressure for freight service. They were among the heaviest locomotives of their type at the time, and one of each were exhibited at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1898. The 4-8-0s introduced piston valves to the Great Northern and could haul 10 cars over the switchbacks without a pusher. This greatly sped up Stevens Pass operations and the Great Northern ordered more of them in 1900.

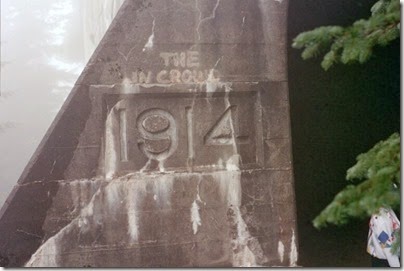

Construction of the 2.63-mile Cascade Tunnel began August 10, 1897, though work on the approaches had started in January. The tunnel with built as quickly as possible, using three shift of workers so construction could proceed 24 hours a day. The tunnel opened in December 1900, eliminating the switchbacks and eliminating the need to add and remove locomotives at Wellington and Cascade Station. It also reduced the maximum grade over Stevens Pass to 2.2% (the tunnel itself has a grade of 1.7% from east to west), reduced the time it took for trains to cross the pass by two hours, and ended the need to remove accumulations of up to 140 feet of snow at the summit every winter. Today, much of the switchbacks are forest service roads, including the road leading from Highway 2 to the Wellington Trailhead.

While the tunnel solved one problem, it ended up creating another. While the tunnel was oriented so that the prevailing west winds of the pass would clear it of smoke from steam locomotives in as little as 20 minutes, if wind was light or coming from another direction, the smoke and heat could be fatal to engine crews and passengers. The railroad tried to combat the problem, but as locomotives became larger and more powerful, the problems got worse. Some locomotives were equipped with extended smokestacks, but this was only partially effective. 200-degree temperatures were recorded in engine cabs, and eventually locomotives were equipped with gas masks.

In 1903, a passenger train with more than 100 passengers stalled in the tunnel when the coupling between the helper engine and the road engine failed. The crews tried to recouple the engines three times without success, and finally the helper engine ran ahead for help. By this time the conditions in the tunnel were seriously affecting the passengers and crew. The conductor reached the engine cab and found the engineer and fireman unconscious, and he collapsed himself before he could do anything. With the entire crew and most of the passengers unconscious, an off-duty railroad fireman traveling on the train as a passenger reached the engine cab and released the air brakes, allowing the train to roll out of the tunnel. Had he then lost consciousness, the train would have continued uncontrolled down the 2.2% mountain grade and eventually derailed, but the fireman managed to remain conscious long enough to make an emergency brake application once the train was in the open at Wellington. He received a citation for his heroic action and a personal check from James J. Hill for $1,000.

Meanwhile, the Great Northern was acquiring larger, more powerful locomotives. Between 1900 and 1906, the GN purchased large numbers of Class F 2-8-0 Consolidations from Rogers, Schenectady, Brooks and Cooke with 41,500 pounds of tractive effort, 175,000 pounds on the drivers and 210 pounds of boiler pressure. Two of the new 2-8-0s, one pulling and one pushing, could handle 1,050 tons at 5 to 6 miles per hour from Skykomish to Cascade Station, increasing freight train length from 25 to 35 or 40 cars. Rogers delivered new 4-6-2 locomotives for passenger service in 1905 and Baldwin delivered more in 1907 and 1909. In 1906, Baldwin delivered five Class L 2-6-6-2 Mallet articulated locomotives for pusher service on Stevens Pass, with 70,000 pounds of tractive effort, 316,000 pounds on the drivers, and 200 pounds of boiler pressure; they also introduced Walschaerts valve gear to the Great Northern. With a 2-8-0 pulling and a new 2-6-6-2 pushing, train tonnage was raised to 1,300 tons. 17 more Mallets were delivered in 1908, and with two Mallets, one pulling and one pushing, train tonnage increased to 1,600 tons.

Between the traffic density and the more powerful locomotives, the Cascade Tunnel was now full of smoke almost all the time, with conditions so hazardous that crews were essentially "flying blind" most of the time. In 1909, the railroad decided to put overhead wires in the tunnel to allow electric locomotives to pull trains through the tunnel.

The electrification system was unusual in that it would be the only three-phase railroad electrification in the Western Hemisphere. The system was chosen because at the time it was the only one that would permit regenerative braking on descending grades, which the railroad planned to use to control speeds on westbound trains in the tunnel. The three-phase system required two trolley wires plus the running rail to serve as the three conductors. Each of the four General Electric locomotives, Nos. 5000-5003, had two streetcar-like trolley poles at each end. Each locomotive had four 500-volt 275-horsepower induction traction motors with double extension shafts and a pinion on each end that meshed with an axle gear; there were two gears on each drive axle. The two two-axle trucks of each locomotive were hinged together with an articulated joint. The locomotives had to run at the speed that corresponded to the 375 rpm speed of the synchronous speed motors, which was 15 miles per hour. At that speed, three electric locomotives could pull a steam locomotive and a 1,600-ton train up the 1.7% grade from Wellington to Cascade Station. A 5,000-kilowatt power plant was built near Leavenworth, and a 33,000-volt transmission line brought power to the substation at the tunnel where it as stepped down to 6,600-volts for the trolley wires. Transformers on the locomotives stepped the power down to 500 volts for the traction motors. The electrification was placed in service on July 10, 1909. On August 11, 1909, both water wheels at the Leavenworth power plant failed and the electrics did not resume operation until September 9.

Historical Photos:

Cascade Tunnel, West Portal, 1910 (UW)

View out end of Cascade Tunnel at Wellington, 1910 (UW)

Electric Locomotives exiting Cascade Tunnel, 1913 (UW)

In 1910, the Great Northern began sending some of its old Cooke, Rogers and Schenectady 2-8-0s to the Baldwin Locomotive Works for rebuilding as M1 2-6-8-0 road Mallets. Baldwin lengthened the boiler and added a new six-coupled engine, moving the two-wheel lead truck forward. The six-coupled engines had low-pressure cylinders with a 35-inch bore and 32-inch stroke. The original 21-inch cylinders from the 2-8-0 were bored out to 23 inches and used as high-pressure cylinders. The resulting Mallet produced 78,000 pounds of tractive effort, had 350,000 pounds on its drivers, and was equipped with a feedwater heater and superheater. In 1911, Great Northern purchased the first of more than 200 3000-series Class O 2-8-2 Mikados with 61,500 pounds of tractive effort. A Mikado could bring a 60 car freight train weighing about 2,500 tons from Seattle to Skykomish, where two of the 2-6-8-0 Mallets would be added as helpers, one placed one-third of the way back and the other two-thirds of the way back. Together the three locomotives could bring the train to Tye in four and a half hours, with only a single 20 minute water stop at Scenic. At the Cascade Tunnel, these trains had to be broken in two, as three electric locomotives were not powerful enough to bring the entire train through the tunnel, and adding a fourth electric locomotive would have overloaded the power plant.

In 1923, the Division Point was moved from Leavenworth 22 miles east to Wenatchee. The time it took to split trains at Tye and reassemble them at Cascade Station had to be eliminated. In order to run four electric locomotives at the same time, the electrical engineers developed a “concatenated” traction motor connection (later known as the “Cascade” connection) that allowed the motors to run at half speed; at half speed four electric locomotives would not overload the power plant. The stop at Tye took only 15 minutes to cut out the 2-6-8-0 helpers. Freight trains, including the Mikado, could be hauled through the tunnel by four electrics, two in the front and two in the middle, in 22 minutes at 7.5 miles per hour. After cutting out the electrics at Cascade Station, the train could reach Wenatchee four hours later, 15 hours after departing Seattle. Passenger trains were pulled through the tunnel by two electrics at 15 miles per hour as before. The result was a surplus of electric motive power that led the Great Northern to consider extending the electrification to Skykomish.

Advancements in electrification technology led Great Northern to replace the original three-phase electrification with an entirely new 11,000-volt single-phase 25-Hertz system using new motor-generator electric locomotives. This system had been pioneered in 1925 by Henry Ford on the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railroad, but this would be the world’s first large-scale installation of this technology. Even though the new 8-mile Cascade Tunnel was starting construction and would soon eliminate the line from Scenic to Berne, Great Northern began installing the new system from Skykomish all the way to Cascade Station in December 1925, and the first of the new locomotives were delivered in 1926. During the installation in the Cascade Tunnel, a single-phase trolley wire was installed between the two three-phase wires, and with temporary short horns on the pantographs of the new electric locomotives, both types could use the tunnel until the changeover was complete. Puget Sound Power & Light provided the power for the new electrification, leasing the Great Northern’s original plant in the Tumwater Canyon which was converted to the new system, and building new plants at Skykomish and Wenatchee. The new electrification was placed in operation between Scenic and Cascade Station on February 27, 1927, and was extended to Skykomish on March 5, 1927.

The new electric locomotives could haul 3,500-ton freight trains from Skykomish to Tye in under two hours. Doubleheaded Mikados brought the train from Seattle to Skykomish, where one Mikado was cut off and an electric was added to each end. Eastbound passenger trains received one electric helper. Westbound trains continued to be steam powered until late 1928, and the electrics returned to Skykomish running light.

Meanwhile, the Great Northern was making additional improvements to the line on the east slope, replacing the original line through Leavenworth and the Tumwater Canyon with a new line called the Chumstick Line at a cost of $5,000,000. Surveys had begun in 1921 and A. Guthrie & Company began construction in July 1927. The new line diverged from the old line west of Wenatchee at Peshastin, proceeded up the Chumstick Valley, passed through the 2,601-foot Chumstick Tunnel into the Wenatchee Valley, crossed the Wenatchee River on a 360-foot steel bridge, passed through an 800-foot tunnel to Dead Horse Canyon, then passed through the 3,960-foot Winton Tunnel to rejoin the original line at Winton. Though this new line was only about a mile shorter than the old line, the maximum grade was reduced from 2.2% to 1.6%, the sharpest curves were 3 degrees instead of nine degrees, and 1,286 degrees of curvature and 1.5 miles of snowsheds were eliminated. The Great Northern decided to electrify this line as well, from Wenatchee to the east portal of the new Cascade Tunnel at Berne. The Chumstick Line and its electrification opened on October 7, 1928, and the Tumwater Canyon line was abandoned, eventually becoming the route of U. S. Highway 2. Leavenworth was bypassed by the main line and was served by a spur off the Chumstick Line.

From the opening of the Chumstick Line to the opening of the new Cascade Tunnel, a period of about three months, there was a gap in the electrification from Berne to Cascade Station, a distance of about 4.5 miles. The Great Northern never electrified this section of the line, which would be abandoned when the new tunnel opened. During those three months, the Great Northern was breaking in new electric locomotives by using them to pull passenger trains from Wenatchee to Berne. At Berne, a Mallet coupled onto the electric and pulled it and its train to Cascade Station, where the electric could again run on its own to Skykomish.

West Portal of the old Cascade Tunnel in 2000.

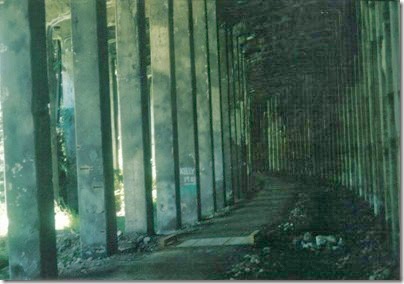

This Cascade Tunnel was abandoned in 1929 with the rest of this route when the new Cascade Tunnel opened between Scenic and Berne on January 12. The land was turned over to the U. S. Forest Service, which blocked the portals of the tunnel for many years. Eventually, the U. S. Government reopened the tunnel and used it as a storehouse for a time, but it had been largely ignored. It was once possible to walk through the tunnel, but a collapse & water buildup inside the tunnel has made it unsafe.

West portal of the old Cascade Tunnel in 2000.

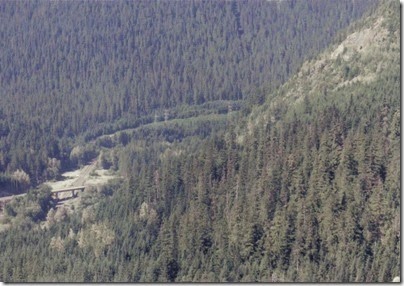

The west portal of the first Cascade Tunnel is visible from Forest Service Road 050 leading to the Wellington Trailhead from the Old Cascade Highway (old Highway 2). This road is part of the old switchback route. Before the Iron Goat Trail was built, this was the closest easy access to this end of the tunnel.

West Portal of the old Cascade Tunnel in 1994.

This 1994 photo was taken from almost the exact same spot as the 2000 photo. In 1994, there was a beaten path down the slope to the portal, but it was very overgrown, and there was water flowing out of the portal.

Continue to Cascade Station…