Thomas Kay Woolen Mill on September 4, 2006

After the Methodist mission was disbanded, Lewis H. Judson and William H. Willson purchased the mission's sawmill and grist mill and put them in the charge of Charles Craft. Craft had come to Oregon in 1845 by way of the Oregon Trail. With the mission closed, Craft was able to live in the nearby Jason Lee House while he managed the mills. Craft also operated a tannery, and he was involved in the creation of the Salem Ditch, a channel designed to divert water from the Santiam River into Mill Creek to provide enough water to keep the mill operating during the summer, when Mill Creek's natural water level was very low.

The Salem Ditch began as a natural trough between what is now Stayton and Aumsville that Lewis H. Judson and William H. Willson located. They determined that the trough could be enhanced to divert water during the summer, giving them a constant source of water power from Mill Creek for year-round milling operation. Oregon's Provisional Government gave them permission to create the diversion channel, and Judson began surveying the project. Progress on the Salem Ditch was slow at first, with various problems delaying construction.

Willamette Woolen Manufacturing Company Mill in 1857

The creation of the Willamette Woolen Manufacturing Company by Joseph Watt and John D. Boon in 1855 pushed the project along, allowing it to be completed in 1856, in time to power the first woolen mill on the west coast, which the Willamette Woolen Manufacturing Company opened in 1857.

With the additional flow in Mill Creek, more industries could be powered by it, but there was only so much room on its banks. In order to make room for more water-powered industries in Salem, the Waller Dam was built in 1864 to divert water from Mill Creek into a manmade channel called a millrace. The millrace diverges from Mill Creek and flows through Salem in a southwesterly direction, emptying into Pringle Creek to the south, just before that creek empties into the Willamette River. Water-powered industries could now be built along the millrace as well, allowing for more industries to make their home in Salem.

Salem-area industries powered by Mill Creek or the millrace included the Salem Capitol Flouring Mills, the Oregon Electric Light Company, the City Ice Works, the Oregon Pulp & Paper Company, the Salem Water Company, the Paulus Brothers Cannery and the Pioneer Oil Company.

Another Salem industry that was powered by the millrace was the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill. Thomas Lister Kay was born in 1837 in Yorkshire, England and was raised in the woolen textile industry. Kay emigrated to America, and initially worked in the woolen trade in New Jersey. He later came to Oregon and was hired as a loom boss at a woolen mill in Brownsville in 1862. Kay moved to Salem in 1888, and purchased the land and millrace rights of the Pioneer Oil Company, a linseed oil mill which had been the first industry to be powered by the millrace when it was established in the 1870s. On this site, Kay built his own woolen mill.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill in 1889

The Thomas Kay Woolen Mill opened in 1889. It was a large wood building, and the machinery inside was powered by a system of belts connected to overhead rotating shafts, which took their power from a turbine that was spun by the flow of water in the millrace. In 1895, a fire destroyed the original building, and the current brick mill building was built the following year.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill on September 4, 2006

Thomas Kay died in 1900, but his mill continued to operate under his family's management until the 1960s. The Thomas Kay Woolen Mill was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 8, 1973 and was designated an American Treasure by the National Park Service in 2004.

Additional Links:

Thomas Kay at Salem Online History

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill on November 11, 2006

The main mill building of the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill was used for various processes. Though the current museum is condensed onto the first two floors, all four floors originally had their own specific use.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill on November 11, 2006

The first floor, or basement, was used for wet and dry finishing, and featured pulling mills, washers, a press and a shear. The second floor was equipped with looms for dressing and weaving. The third floor with carders and spinning mules was used for the carding and spinning processes, and the fourth floor drying loft was for the tentering, or air drying, of fabric.

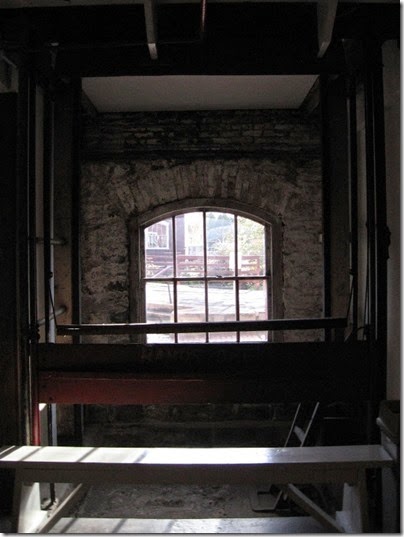

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Elevator Shaft on November 11, 2006

The four floors of the main mill building were connected by an elevator that, like the rest of the machinery at the mill, took its power from the drive shaft connected to the water-powered turbine. The elevator transported loose wool, unfinished wool and partially-finished wool from one floor to another.

The Salem Oregon Community Guide has an excellent tour of the inside of the main mill building and its equipment. Click here to see their tour.

Historical Photos:

Portrait of Thomas Kay (Oregon State Library)

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill (Oregon State Library)

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill (Oregon State Library)

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill, circa 1905 (Salem Public Library)

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill, 1910 (Salem Public Library)

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill, 1937 (Salem Public Library)

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill, circa 1950 (Salem Public Library)

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill, 1959 (Salem Public Library)

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill, 1960 (Salem Public Library)

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill, 1992 (Salem Public Library)

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill on November 11, 2006

Before most wool ever made its way to the main building, it went through various processes in the mill's accessory buildings first.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Warehouse on November 11, 2006

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Warehouse on November 11, 2006

Just about any industry employed the use of a warehouse, and the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill was no exception.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Warehouse on November 11, 2006

The warehouse building was divided into three main sections: the Rag Warehouse, the Stock Warehouse and the Wool Warehouse.

Wool Warehouse on November 11, 2006

Today, The warehouse building serves as the main entrance for the Mission Mill Museum.

Wool Warehouse on November 11, 2006

The Wool Warehouse contains a café.

Stock Warehouse on November 11, 2006

The Stock Warehouse contains retail shops and visitor information.

Rag Warehouse on November 11, 2006

The Rag Warehouse is used as law offices.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Picker House on November 11, 2006

A sheep's wool picks up debris such as burrs, seeds, twigs, leaves and straw naturally as the sheep goes about its life on the farm. These items had to be removed from the wool before it could continue in the milling process, as the debris could damage the machinery. Inside the unheated and poorly-lit 19th century brick Picker House, raw wool was put through an English Standard Picker called "Big Ben" to pick out the debris. Used 100% wool rags also came through the picker house, going through a Clark & Sons picker machine. These rags would be shredded for use as shoddy, a wool fiber that was mixed with virgin wool for fabric production (an early form of recycling).

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Scouring Room on November 11, 2006

A number of important processes took place in the Dye House and its Scouring Room before the wool could be sent to the main mill. Even after picking, domestic wool still contains impurities like dirt, lanolin and the sheep's perspiration. These impurities, which make up about 60% of domestic raw wool, is removed by scouring.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Scouring Room on November 11, 2006

The Thomas Kay mill used a C. G. Sargent scouring train that used a soap and alkali solution and oscillating forks, rakes and squeeze rollers to mechanically clean the fleece.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Dye House on November 11, 2006

Another process that took place in the dye house was carbonization, a chemical process that removed all remaining traces of vegetable matter form the wool. Wool rags were also carbonized before being used for shoddy. After carbonizing, wool and rags were pounded to increase thickness. The main process in the dye house was, of course, dyeing the wool. Dyes were mixed into water by hand by the dyemaster in large wooden vats and heated with steam, then chemicals like chrome and sulfuric acid, also known as Vitrol, were added. The dye house was hot, steamy, wet, and smelly and although steam was vented out through the louvered cupolas in the roof, it was still usually warm enough to create fog on winter days. The dyeing process took about three hours per batch. After dyeing, the dye baths were dumped into the millrace, leading to the rumor that an outsider could tell what color fabric was being made by the color of the water in the millrace.

Reconstruction of the Dye House was provided through funding from the Oregon State Historic Preservation Office, Portland General Electric, the Salem Foundation, U. S. National Bank, Pacific Northwest Bell and Willamette Industries.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Boiler Room on November 11, 2006

The Thomas Kay Woolen Mill's need for heat, hot water and steam necessitated a Boiler Room. The Boiler Room is off-limits to the general public, but here is the entrance.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Machine Shop on November 11, 2006

As with any machinery, the equipment at the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill was subject to periodic maintenance and repairs, which was taking place constantly somewhere in the mill. In the days before highways and air freight, spare parts for these machines had to be made from scratch on-site by the millwright in the machine shop.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Machine Shop on November 11, 2006

The machine shop contained the equipment like a lathe, drill press and saws, all driven by belts connected to the drive shaft to the turbine, as well as a forge and all the hand tools and other materials needed to keep the mill operating.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Machine Shop on November 11, 2006

The Mentzer Machine Shop was dedicated October 4, 1986 in memory of Wayne Mentzer, who was the millwright for the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill from 1924 to 1984.

Millrace at the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill on November 11, 2006

Salem's millrace flows through the middle of the Mission Mill site, and all of the machinery at the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill was originally powered by a turbine driven by the flow of water in the millrace. The mill was powered entirely by water power until 1940, when a supplementary generator was added. The water power system is located in the wheel house near the dye house, which remains almost exactly as it was when the mill was in operation.

Turbine at the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill on November 11, 2006

A turbine is a type of horizontal water wheel that harnesses potential energy from falling water from the millrace. At the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill, water falls from a height of 12 feet into the top of the turbine. The force of the water falling against the blades causes the turbine to spin. The rotating shaft in the center of the turbine transfers this energy to the rest of the mill.

Turbine at the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill on November 11, 2006

For most of its history, the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill was powered by a 1914 Samson 45 turbine like this one made by James Leffel & Company.

James Leffel & Company Samson Size 45 Turbine

The Mission Mill's turbine is still in place, and though it has been severed from the drive shaft and small motors now power the museum's restored machinery, the turbine is connected to a generator and still produces up to 20 kilowatts of electricity, enough to light 200 100-watt light bulbs or run 12 computers, which is sold back to Portland General Electric.

The Thomas Kay Woolen Mill's turbine is the only vintage turbine in the western United States that still generates power from a millrace.

Thomas Kay Woolen Mill Crown Gears on November 11, 2006

The turbine is connected to a vertical shaft that leads to the crown gears, which transferred the power from the vertical shaft to the horizontal shaft that led to the main mill building. The crown gears no longer connected to this vertical shaft, and although the crown gears were motionless when I was there, they are apparently connected to the generator the produces electricity from the turbine.

Water Power Interpretive Exhibit on November 11, 2006

The actual turbine that powered the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill cannot be seen, and the crown gears are no longer connected to the shafts throughout the mill. In order to explain how the turbine used water to generate power, and how it is then transferred to the machinery, Portland General Electric built a Water Power Interpretive Exhibit in 1999.

“Water Power In Action” model on November 11, 2006

“Water Power in Action” model diagram

The Water Power Interpretive Exhibit features a "Water Power in Action" model that shows how power from the crown gears is transferred to the mill machinery The crown gears are connected to a main drive shaft. This shaft is connected to the machinery by various pulleys, belts and gears. As the above diagram and the pictures illustrate, the model shows the main drive shaft powering fans, the elevator, and an electrical generator that provided electric power for lighting. The main drive shaft also powered all of the mill's machinery and the large tools in the machine shop.

“Water Power in Action” model on November 11, 2006

The following video shows the "Water Power in Action" model "in action," with the fans, elevator and generator actually being powered by the main drive shaft.

Continue to 2F: Marion County Historical Society…

No comments:

Post a Comment